Why exploitation of care workers is likely to persist, despite plunge in visa numbers

The number of work visas issued by the Home Office between Q4 2023 and Q1 2024 plummeted by 35%, according to the latest Home Office immigration statistics. This was driven by an 84% reduction in visas issued to carers, partly resulting from the government's decision to ban them from bringing family members to the UK. However, increasing recruitment of carers from so-called ‘red-list’ countries means exploitation of migrant workers in the care sector is likely to persist.

Work visa numbers have steadily dropped for two consecutive quarters

Since the end of free movement, there has been a sharp increase in the number of work visas issued to main applicants, in order to fill labour market gaps and keep the economy globally competitive. However, following a peak of 68,000 work visas issued in Q3 2023, numbers have been steadily dropping, first to 49,000 in Q4 2023 and then down to just 32,000 in Q1 2024 (see Figure 1).

This trend can be explained by a sharp drop in Health and Care Worker visas granted, from 45,000 in Q3 2023 to just 9,000 this past quarter. Specifically, it was care workers who drove the trend.

Figure 1. Work visas issued to main applicants - main categories

International recruitment of care workers has plummeted this quarter

Between Q4 2023 and Q1 2024, there has been an 84% decrease in visas issued to care and senior care workers, from 20,188 to just 3,303 (see Figure 2). There are three possible reasons for this decline.

Figure 2. Visas issued to main applicants - care and senior care workers

First, in December 2023 the Home Office announced two major changes to the Health and Care Worker visa:

- New care and senior care workers could no longer bring dependants;

- Only CQC-registered providers in England could sponsor workers.

In anticipation of these changes, which were enacted from 11 March 2024, it is possible that fewer care workers considered the UK as an attractive destination from December onwards.

Second, the Home Office may have started to scrutinise visa applications more rigorously, following widespread reports of migrant labour exploitation in social care.

Finally, not all employers have sponsor licences. Those that do could have either filled most vacancies or been able to rely on care workers already in the UK, particularly migrant care workers left without work and individuals switching from Student and Graduate visas (although this release does not have data for Q1 2024).

A decline in work visas does not alleviate risks of exploitation

Despite the sharp decline in the number of work visas issued, the risk of labour exploitation persists. First, a look at migrant care workers’ countries of origin suggests a majority share of high-risk countries. Second, latest data shows that enforcement action levels are not sufficient to adequately enforce Home Office standards for sponsors of migrant workers. Let’s look at this in more detail.

‘Red and amber list’ countries make up an increasing share of health and care recruitment

Countries marked as red or amber (according to government’s own code of practice for international recruitment in health and social care in England and based on World Health Organisation (WHO) guidance) should not be recruited from, even if individuals can apply for visas on their own accord. This is because such countries have pressing labour shortages that prevent them from achieving universal healthcare coverage, and recruitment would drain away an already thin pool of skilled workers.

With the exception of Nepal, the UK currently has no Memorandum of Understanding with any of the other 54 ‘red-list’ countries. While far from a panacea, the importance of having Memorandums of Understanding is that they are government-to-government agreements that support the ethical recruitment of workers, by creating fair, well-regulated hiring frameworks.

Without these safeguards, predatory recruitment practices are more likely to be widespread. ‘Red-list’ countries are particularly affected by predatory recruiters, because migration ‘push’ factors are stronger for workers who seek to move to the UK from countries with crippling healthcare infrastructure and endemic understaffing. Despite this, an increasing and, in fact, majority share of the international workforce has come from such countries since the launch of the Health and Care Worker visa.

Figure 3. Visas issued to care and senior care workers, by nationality.

In the absence of ethical recruitment channels, there is mounting evidence that workers from ‘red-list’ countries have to pay recruitment fees to intermediaries, who make a hefty business of connecting them with employers in the UK. The relative price of obtaining a UK visa is also higher in ‘red-list’ countries (which have lower median incomes, causing workers to take on debt just to fund their relocation costs, even where they don’t pay recruiters.

Examples of this abound. Some of our clients paid as much as £20,000 in recruitment fees. Separately, research by the Modern Slavery Policy and Evidence Centre has found “significant issues of debt [...] which are both associated with illegal recruitment fees, and can arise from travel, training and accommodation costs, and high visa application fees”.

Consequently, workers end up placing all eggs in one basket - their UK care job - just to pay off debts and then, hopefully, earn some money. The issue is that unscrupulous visa sponsors are able to impose unfavourable working conditions upon migrant carers, in the knowledge that the workers’ livelihoods depend on this one job.

The risk of exploitation derived from debt is exacerbated by the imbalance of power inherent in visa systems that tie migrant workers to their employers. Under the work sponsorship system, workers are legally tied to their visa sponsors, with limited and costly options to switch visas in-country. This prompts workers to acquiesce to precarious conditions in their workplaces. As research from Citizens Advice recently highlighted, “the combination of a highly restrictive work visa and a sector where workers regularly face poor treatment has led to almost weekly news reports of migrant care workers being exploited.”

Home Office action against sponsors lags behind

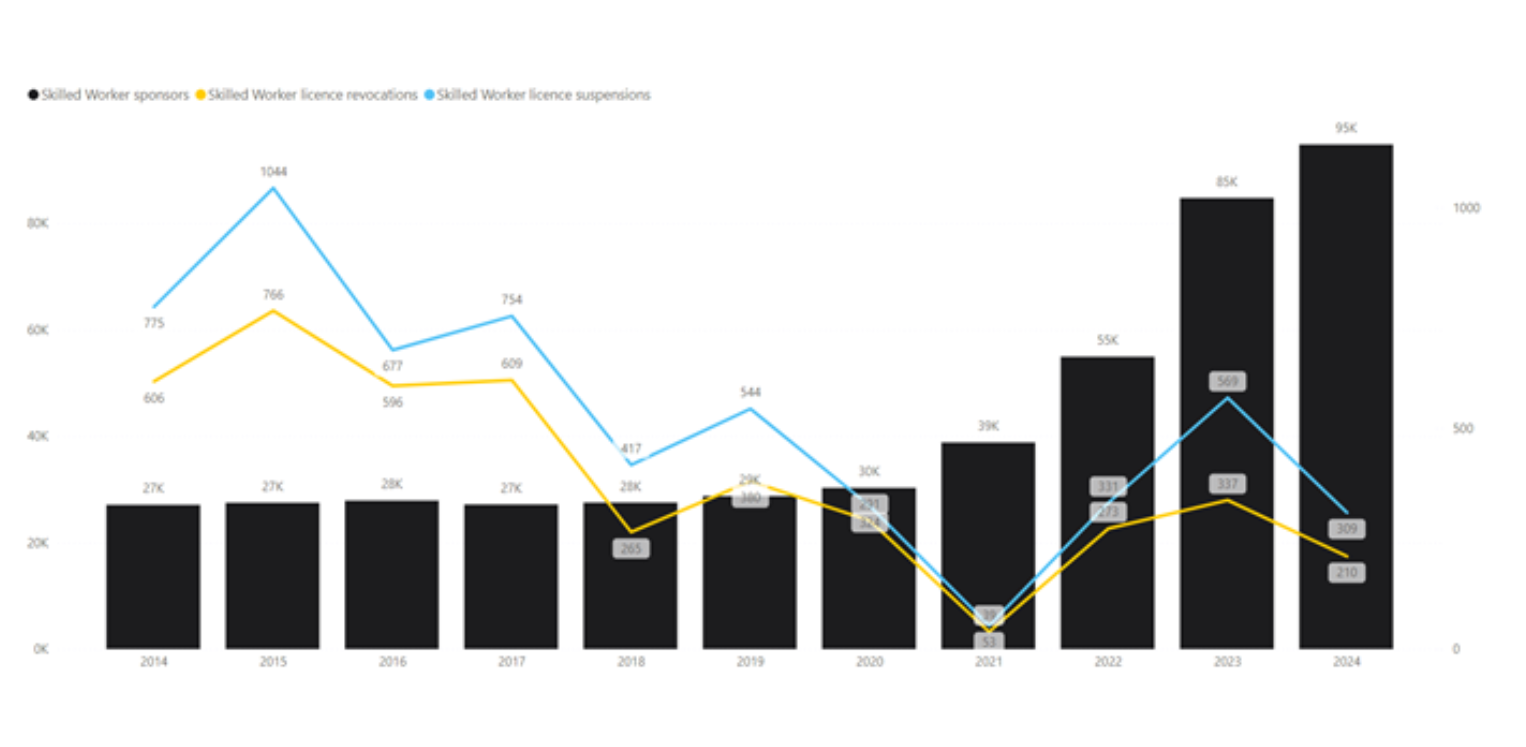

The Home Office has also failed to adequately regulate sponsor activity and punish rogue sponsors, including those who exploit their workers. Sponsorship data show that the Home Office has increased its enforcement activity in Q1 2024, relative to annual totals for the previous couple of years (see Figure 4). However, as we’ve noted before, it is simply not enough given the burgeoning number of businesses licenced to sponsor workers from abroad.

Figure 4. Suspensions and revocations of Skilled Worker sponsor licences

Nevertheless, we warn that dramatically increasing enforcement activity must come hand-in-hand with safeguards for sponsored workers themselves. At present, these safeguards are very weak, as underscored in the recent Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration (ICIBI) report. Workers whose sponsor loses their licence, will have their visas curtailed, with just 60 days to find a new sponsor and apply for a visa. Not only is this unreasonably harsh in relation to workers themselves, it also inhibits reporting of exploitation across the sector for fear of immigration consequences.

Please donate

To support the Work Rights Centre in our efforts to assist migrant workers please consider making a donation